wow so cool, like unicorns of the sea!

Narwhal

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the species of whale. For the class of submarine, see

Narwhal class submarine.

Narwhal

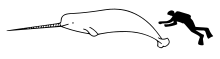

[1]

Size comparison with an average human

Conservation status

Near Threatened (

IUCN 3.1)

[2]

Scientific classification

Kingdom:

Animalia

Phylum:

Chordata

Class:

Mammalia

Order:

Cetacea

Suborder:

Odontoceti

Family:

Monodontidae

Genus:

Monodon

Linnaeus, 1758

Species:

M. monoceros

Binomial name

Monodon monoceros

Linnaeus,

1758

Narwhal range (in blue)

The

narwhal, or

narwhale,

Monodon monoceros, is a medium-sized

toothed whale that lives year-round in the

Arctic. One of two living species of

whale in the

Monodontidae family, along with the

beluga whale, the narwhal males are distinguished by a characteristic long, straight,

helical tusk extending from their upper left jaw. Found primarily in

Canadian Arctic and

Greenlandic waters, rarely south of

65°N latitude, the narwhal is a uniquely specialized Arctic predator. In the winter, it feeds on

benthic prey, mostly

flatfish, at depths of up to 1500 m under dense

pack ice.

[3] Narwhal have been harvested for over a thousand years by

Inuit people in northern Canada and Greenland for

meat and

ivory,

and a regulated subsistence hunt continues to this day. While

populations appear stable, the narwhal has been deemed particularly

vulnerable to

climate change due to a narrow geographical range and specialized diet.

[4]

Contents

[

hide]

Taxonomy and etymology

The narwhal was one of the many species originally described by

Linnaeus in his

Systema Naturae.

[5] Its name is derived from the

Old Norse word

nár, meaning "corpse", in reference to the animal's greyish, mottled

pigmentation, like that of a drowned sailor.

[6] The scientific name,

Monodon monoceros, is derived from

Greek: "one-tooth one-horn"

[6] or "one-toothed unicorn".

The narwhal is most closely related to the

beluga whale. Together, these two species comprise the only extant members of the

Monodontidae

family, sometimes referred to as the "white whales". The Monodontidae

are distinguished by medium size (3-5 m in length), forehead

melons, short snouts, and the absence of a true dorsal fin.

[7] The white whales,

dolphins (Delphinidae) and

porpoises (Phocoenidae) together comprise the

Delphinoidea superfamily, which are of likely

monophyletic

origin. Genetic evidence suggests the porpoises are more closely

related to the white whales, and that these two families constitute a

separate

clade which diverged from the Delphinoidea within the past 11 million years.

[8]

Description

This narwhal skull has double

tusks,

a rare trait in narwhals. Usually, males have a single long tusk

protruding from the incisor on the left side of the upper jaw.

(Zoologisches Museum in Hamburg)

Male narwhals weigh up to 1,600 kilograms (3,500

lb),

and the females weigh around 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). The

pigmentation of the narwhal is a mottled black and white pattern. They

are darkest when born and become whiter in color with age.

[6][9]

The most conspicuous characteristic of the male narwhal is its single 2–3 meter (7–10 ft) long

tusk, an

incisor tooth that projects from the left side of the upper jaw and forms a left-handed

helix.

The tusk can be up to 3 meters (9.8 ft) long—compared with a body

length of 4–5 meters (13–16 ft)—and weigh up to 10 kilograms (22 lb).

About one in 500 males has two tusks, which occurs when the right

incisor, normally small, also grows out. A female narwhal has a shorter,

and straighter tusk.

[10] She may also produce a second tusk, but this occurs rarely, and there is a single recorded case of a female with dual tusks.

[11]

The most broadly accepted theory for the role of the tusk is as a

secondary sexual characteristic, similar to the mane of a

lion or the tail feathers of a

peacock.

[6] This hypothesis was notably discussed and defended at length by

Charles Darwin, in

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex

(1871). It may help determine social rank, maintain dominance

hierarchies, or help young males develop skills necessary for

performance in adult sexual roles. Narwhals have rarely been observed

using their tusk for fighting,

[12] other aggressive behavior or for breaking sea ice in their Arctic habitat.

[6]

Behavior and diet

Narwhals "tusking"

Narwhals have a relatively restricted and specialized diet. Their prey is predominantly composed of

Greenland halibut,

polar and

Arctic cod,

shrimp and

Gonatus squid. Additional items found in stomachs have included

wolffish,

capelin,

skate eggs and sometimes rocks, accidentally ingested when whales feed near the bottom.

[3][13][14]

Narwhals exhibit seasonal migrations, with high fidelity of return to

preferred, ice-free summering grounds, usually in shallow waters. In

the winter, they are found primarily in offshore, deeper waters under

thick pack ice, surfacing in narrow fissures in the sea ice, or

leads.

[14]

Narwhals from Canada and West Greenland winter regularly in the pack

ice of Davis Strait and Baffin Bay along the continental slope with less

than 5% open water and high densities of Greenland halibut.

[3] Feeding in the winter accounts for a much larger portion of narwhal energy intake than in the summer

[3][14] and, as marine predators, they are unique in their successful exploitation of deep-water arctic ecosystems.

Most notable of their adaptations is the ability to perform deep

dives. When on their wintering grounds, the narwhals make some of the

deepest dives ever recorded for a marine mammal, diving to at least 800

meters (2,625 feet) over 15 times per day, with many dives reaching

1,500 meters (4,921 feet). Dives to these depths last around 25 minutes,

including the time spent at the bottom and the transit down and back

from the surface.

[15] In the shallower summering grounds, narwhals dive to depths between 30 and 300 meters (90–900 feet).

Narwhals normally congregate in groups of about five to ten

individuals. In the summer, several groups come together, forming larger

aggregations. At times, male narwhals rub their tusks together in an

activity called "tusking".

[13] This behavior is thought to maintain social dominance hierarchies.

[13]

Population and distribution

The frequent (solid) and rare (striped) occurrence of narwhal populations

The narwhal is found predominantly in the Atlantic and

Russian areas of the Arctic Ocean. Individuals are commonly recorded in the northern part of

Hudson Bay,

Hudson Strait,

Baffin Bay; off the east coast of

Greenland; and in a strip running east from the northern end of Greenland round to eastern Russia (

170° East). Land in this strip includes

Svalbard,

Franz Joseph Land, and

Severnaya Zemlya.

[6] The northernmost sightings of narwhal have occurred north of Franz Joseph Land, at about

85° North latitude.

[6]

The world population is currently estimated to be around 75,000 individuals.

[4] Most of the world's narwhals are concentrated in the

fjords and inlets of

Northern Canada and western Greenland.

Narwhals are a

migratory

species. In summer months, they move closer to coasts, usually in pods

of 10-100. As the winter freeze begins, they move away from shore, and

reside in densely packed ice, surviving in

leads and small holes in the ice. As

spring comes, these leads open up into channels and the narwhals return to the coastal

bays.

[4]

Predation and conservation

The only predators of narwhals besides humans are

polar bears and

killer whales (orcas).

Inuit people are allowed to

hunt this whale species legally for

subsistence. The northern climate provides little nutrition in the form of

vitamins, which can only be obtained through the consumption of

seal, whale, and

walrus. Almost all parts of the narwhal, meat, skin, blubber and organs are consumed.

Mattak, the name for raw skin and blubber, is considered a delicacy, and the bones are used for tools and art.

[6] In some places in Greenland, such as

Qaanaaq, traditional hunting methods are used, and whales are harpooned from handmade

kayaks. In other parts of Greenland and

Northern Canada, high-speed

boats and

hunting rifles are used.

[6]

The head of a lance made from a Narwhal tusk with a meteorite iron blade

Narwhal have been found to be one of the most vulnerable arctic

marine mammals to climate change. The study quantified the

vulnerabilities of 11 year-round Arctic sea mammals.

[4][16] Narwhals that have been brought into captivity tend to die of unnatural causes.

[17]

Humans and narwhals

In

Inuit legend, the narwhal's tusk was created when a woman with a

harpoon

rope tied around her waist was dragged into the ocean after the harpoon

had struck a large narwhal. She was transformed into a narwhal herself,

and her hair, which she was wearing in a twisted knot, became the

characteristic spiral narwhal tusk.

[18]

Image of narwhal from

Brehms Tierleben

Some

medieval Europeans believed narwhal tusks to be the horns from the legendary

unicorn.

[19] As these horns were considered to have

magic powers, such as the ability to cure poison and

melancholia,

Vikings and other northern traders were able to sell them for many times their weight in

gold.

The tusks were used to make cups that were thought to negate any poison

that may have been slipped into the drink. During the 16th century,

Queen Elizabeth received a carved and bejeweled narwhal tusk for

£10,000—the cost of a castle (approximately £1.5—2.5 Million in 2007, using the

retail price index).

[20] The tusks were staples of the

cabinet of curiosities.

[21] The truth of the tusk's origin developed gradually during the

Age of Exploration, as explorers and naturalists began to visit Arctic regions themselves. In 1555,

Olaus Magnus published a drawing of a fish-like creature with a horn on its forehead, correctly identifying it as a "Narwal".

[21] The narwhal was one of two possible explanations of the giant sea phenomenon written by

Jules Verne in his book

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. The other possible explanation was a man-made vessel, but that was not likely in the opinion of the narrator.

Herman Melville wrote a section on the narwhal in

Moby Dick, in which he claims a narwhal tusk hung for "a long period" in

Windsor Castle after

Sir Martin Frobisher had given it to

Queen Elizabeth.

[22]